ELECTIVES

Introduction to Sports Journalism

JOUR1095: Special Topics

This course is open to all majors and will introduce students to the history of sports reporting, the evolution of sports media, the influence of sports on culture, and the fundamentals of sports journalism -- including sourcing, interviewing, writing and production of sports stories on various platforms. Instructor is Steve Buckheit, an award-winning features producer at ESPN.

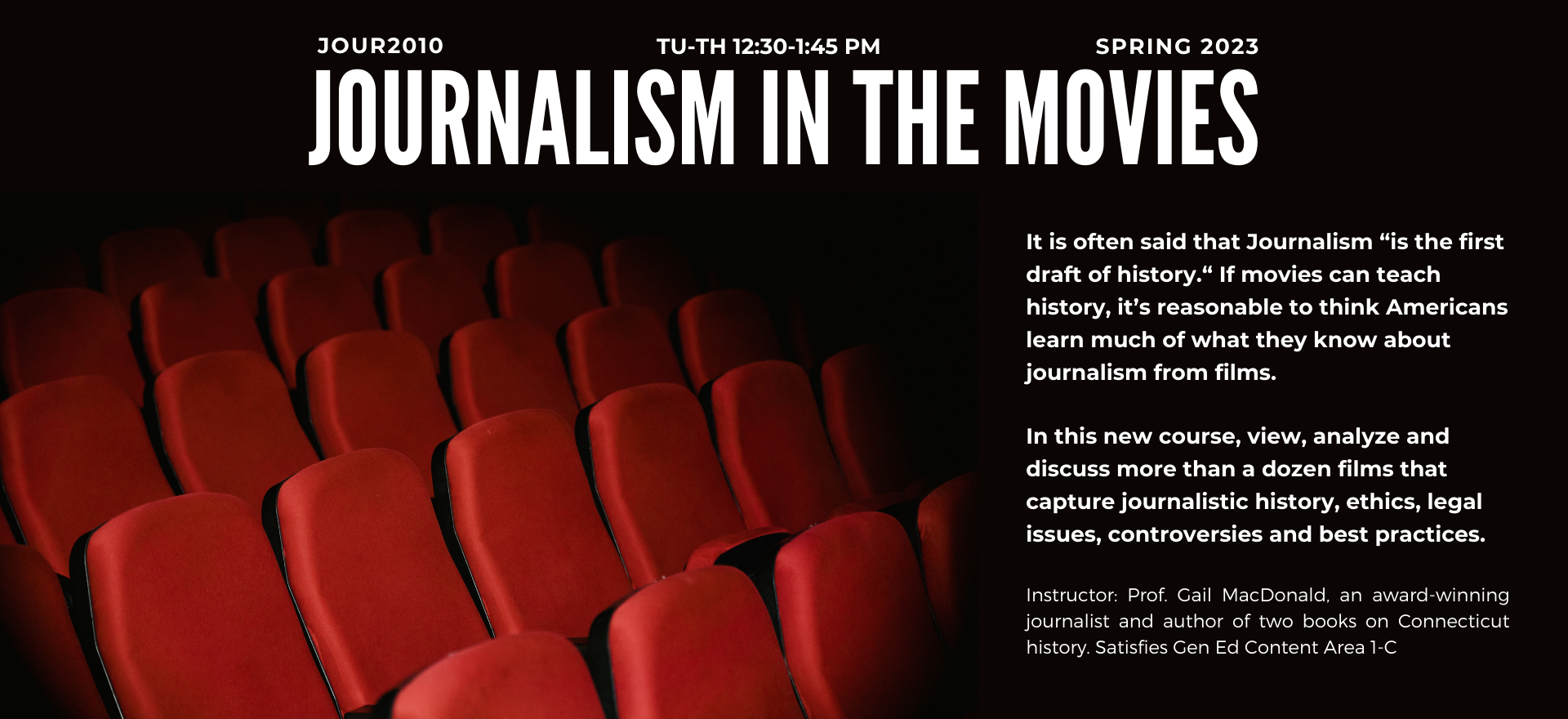

Journalism in the Movies

JOUR2010 (CA-1)

Open to all majors. Students will watch and discuss motion pictures with journalism themes. Many of the films are about important cases in journalism, U.S. and international history. The rest are fictional representations of journalistic stories and scenarios. Themes from the films that will be examined include: the nature of news, historical development of the press, journalism ethics and law, diversity in the news, newsroom dynamics and relationships, and the fields of broadcast and investigative journalism. The course satisfies a General Education requirement for history.

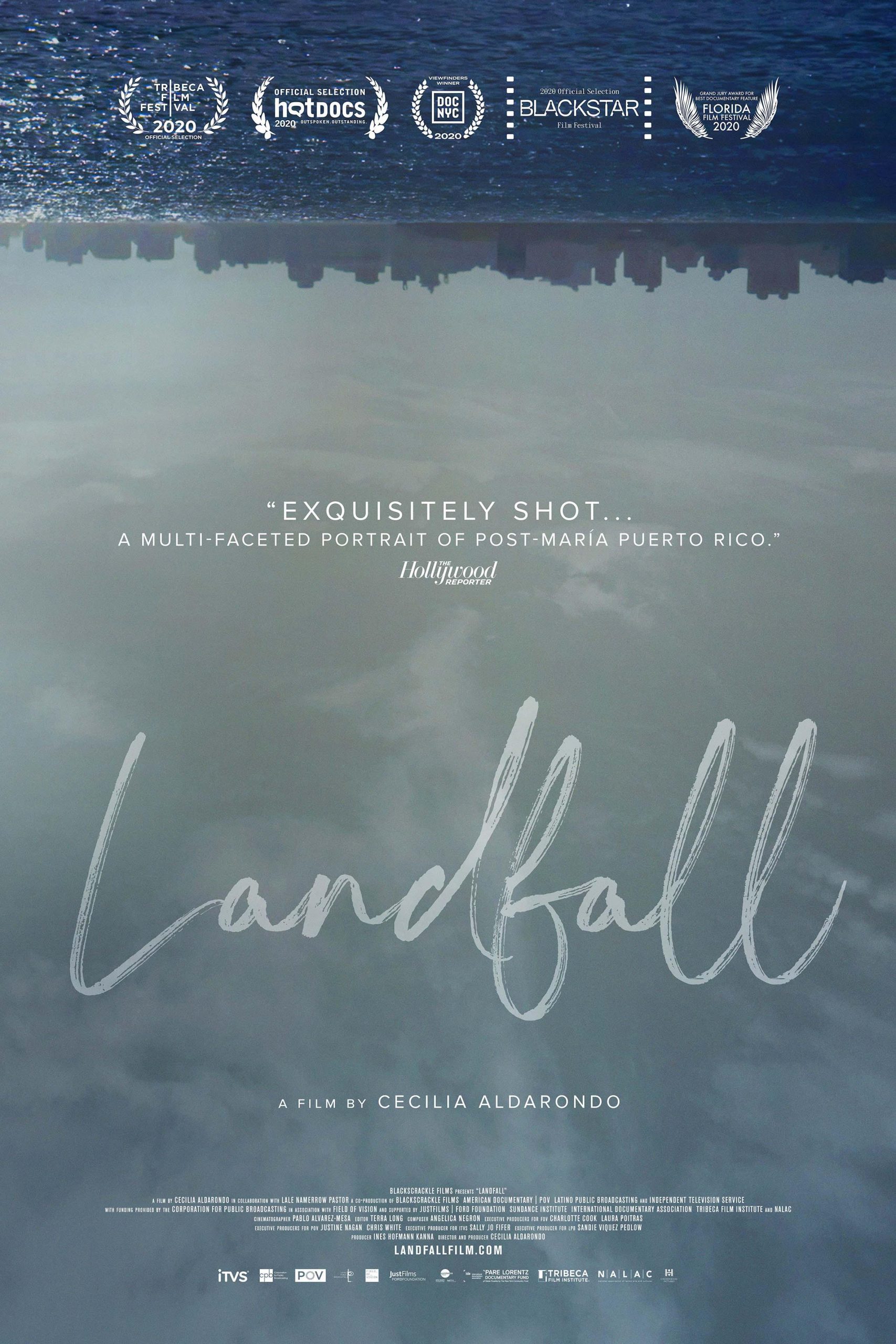

Art of the Interview in Documentary Film

JOUR2095: Special Topics

This production course will explore approaches to navigating the technical and ethical considerations of preparing for and conducting filmed interviews. Develop essential tools of documentary film production, such as research, interview aesthetics and formal approaches, and post-production uses of recorded interviews. Coursework will provide students with a range of long-form and short-form documentaries, from intimate direct to camera interviews to talking heads. Students will work independently and collaboratively on interview assignments and exercises that deepen their communication and understanding of how recorded interviews drive narratives forward.

TV & Video News Programming

JOUR2095: Special Topics

This course teaches students the steps required to build an online video or TV newscast. It is excellent preparation for students who plan to work in broadcast, cable or online news. Learning how a recurring news program is built, planned and executed is also important preparation for students who plan entrepreneurial endeavors or who may be called upon to produce video programming in a recurring format for social service organizations or commercial industry. This course may be of particular interest to students who plan to take advanced courses in audio and video journalism, podcasting, or to those who intend to participate in UCTV.

Feature Writing

JOUR3012W

Feature writing is the art of storytelling. It contains the elements of fiction writing –vivid scenes, strong characters, a narrative arc –but is grounded in dogged reporting and sharp observation. It can be off-beat or topical, funny or sad. Unlike a straight news story that simply presents the facts, a good feature goes beyond to put those facts into some larger context and provide deeper meaning. A good feature is imaginative, original and authentic. This class will teach you how to write features, from developing ideas to effective reporting and interviewing skills to organizing and writing stories. Students will explore different types of features, including profiles, trend stories and human-interest stories. Students will learn by doing, by writing and re-writing, by reading lots of features and dissecting one another’s work.

Design for Digital Journalists

JOUR3031

This course introduces editorial design to journalism students. Learn the fundamentals of visual communication design as applied to modern media. Topics include design principles, aesthetics, social media, intuitive design, typography, layout, photo editing, color theory, motion graphics, and informational graphics. Think critically and creatively about designing material for diverse audiences. Learn how to assess and critique visual journalism work.

Newswriting for Broadcast & Digital

JOUR3040: (formerly Audio & Video Reporting and Writing)

Application of newswriting and news reporting techniques for broadcast, digital video and digital audio. Practical use of digital media recording equipment and professional audio/video editing software.

Reporting & Editing TV News

JOUR3041

This is an advanced broadcast journalism class that teaches students how to gather, edit and deliver accurate, newsworthy information for television newscasts. Students develop the skills needed to report news and organize newscasts through actual experience in and out of class.

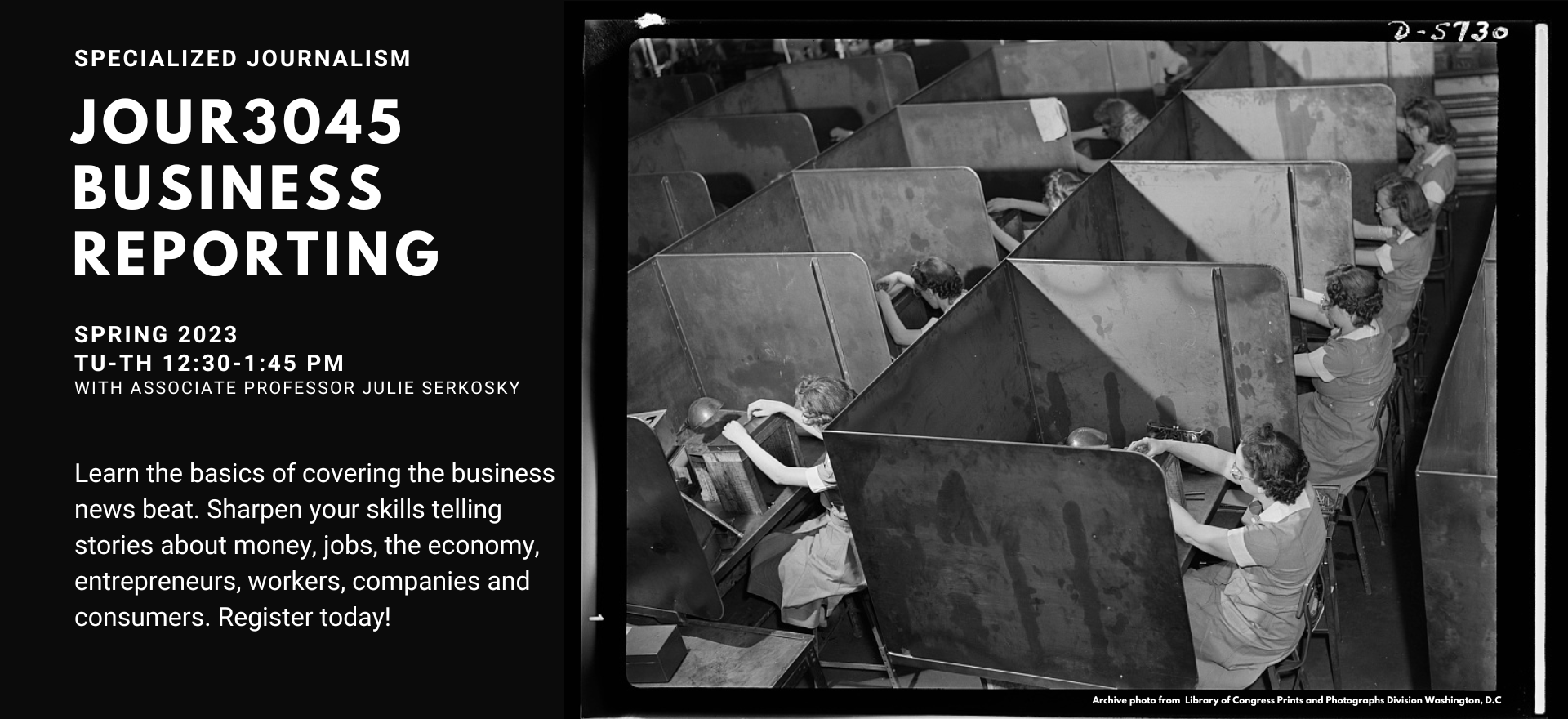

Business Reporting

JOUR3045: Specialized Journalism

Learn the basics of the business and financial news beat. Sharpen your skills telling stories about money, jobs, the economy, entrepreneurs, workers and labor unions, companies and consumers.

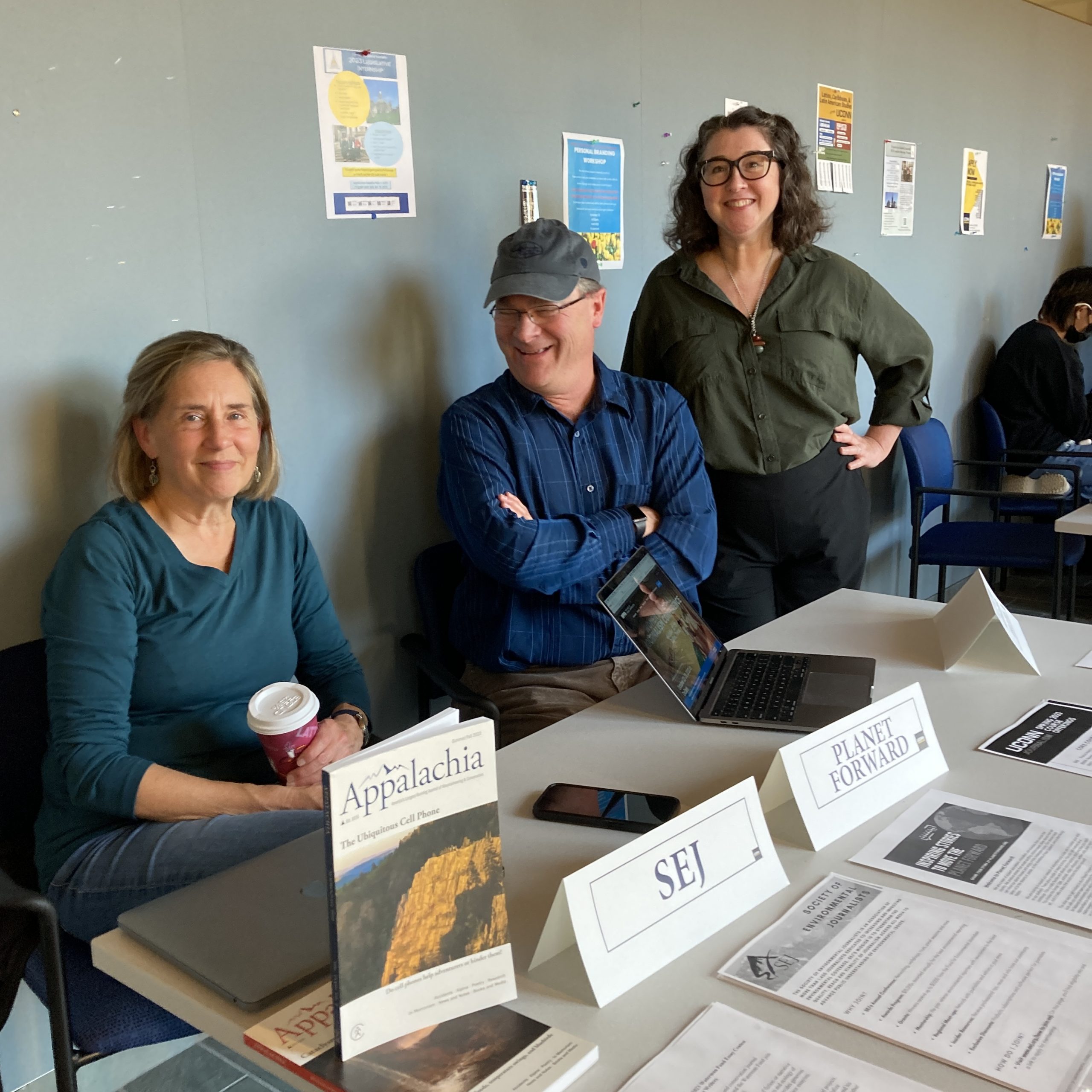

Environmental Journalism

JOUR3046

Explores specialized coverage of environmental issues by journalists, emphasizing news reporting with the opportunity to produce print, visual and multimedia news reports.

Visual Journalism

JOUR3065

Examines current trends in visual digital journalism; develops skills in photojournalism, multimedia and video storytelling. Instructor approved digital camera required.

Black Documentary Film Archival Practices

JOUR3575/AFRA3575

Critical and historical examination of Black American archival usage through documentary films and media.

Video Storytelling

JOUR4065 (formerly Advanced Visual Journalism)

Explores journalistic storytelling techniques through video. Students will learn how to gather video and audio content and develop production and post-production techniques to create and publish extended narrative multimedia projects.

Supervised Field Internship

JOUR4091

After her top-10 finish in the 10K final at the 2021 Olympic trials, Emily Durgin ’17 (CLAS), who won nine American Athletic Conference individual championships at UConn while earning her journalism and communications degree, decided to take it up a notch.

After her top-10 finish in the 10K final at the 2021 Olympic trials, Emily Durgin ’17 (CLAS), who won nine American Athletic Conference individual championships at UConn while earning her journalism and communications degree, decided to take it up a notch.