In 1991 in Pakistan, there was a surge of women being burned.

A stove would burst, the official report would say – a terrible accident – and only the young bride of the family would be injured or, more often, killed.

“It was very intriguing for me,” says Marvi Sirmed, a journalist and activist who was one of the rare young women working at a newspaper in Pakistan at the time. “When I started digging, first they said, ‘Oh, you know, because in the kitchen, only the daughter-in-law works, so everyone else remains unhurt.’”

Most newspapers in Pakistan at that time employed only one woman, says Sirmed, and that woman was known as the “lady reporter” who would exclusively write for women. Articles about the latest fashions, or recipes, or romantic short stories were the sorts of topics that women in the patriarchal society should be reading, according to the men who ran the newspapers.

Sirmed, who was working as the editor of her newspaper’s weekly women’s edition, felt otherwise.

“I kept digging for four or five months for this story, and some of these incidents would be accidental,” she says, “but most of it was because the daughter-in-law did not bring enough dowry. So, it was a dowry killing, or an honor killing, concealed into accident.”

Her enterprising journalism was not welcomed.

“I brought several stories of the survivors of these ‘accidents,’ and my editor just refused to entertain that,” she says. “He said that women buy the women’s edition because they want to read more about the pleasant subjects. But what you are doing is exactly what they don’t want to know and what we don't want to put in our publication, because these are not pretty faces. If you want to do a modeling session with a high-ranking model girl who would display good apparel, we are all for it. But these faces of burned women, it’s absolutely a ‘no’ story.”

The stories of the burned women were far from the last time Sirmed would face opposition, controversy, harassment, personal attacks, and outright violence for the stories she wanted to tell and the light she aimed to shine on some of the darkest corners of Pakistani life and governance.

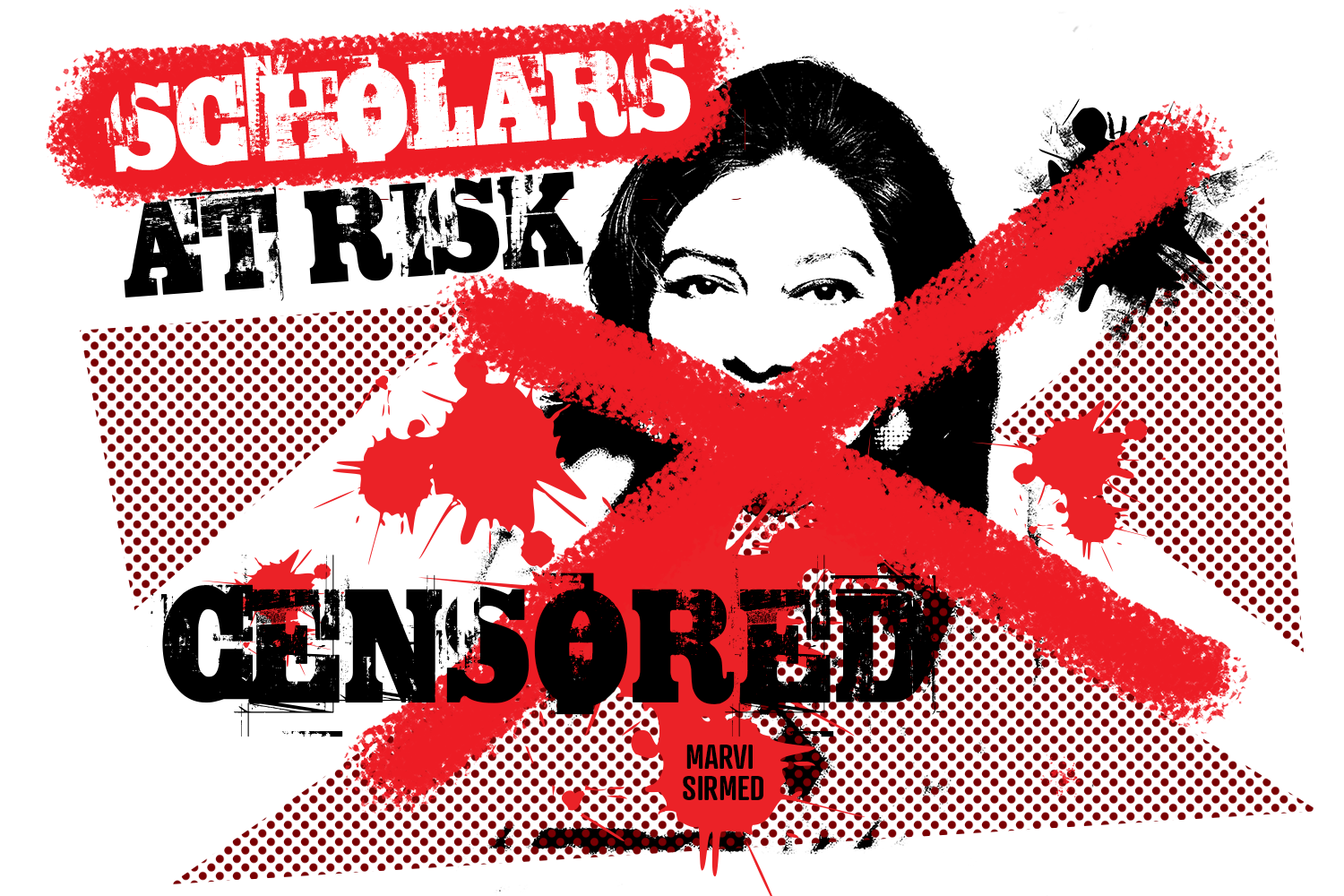

In fact, she’s still telling those stories, and working as an activist for change in Pakistan and other South Asian countries, though she’s now more than 7,000 miles away from her home country, in the United States and teaching at UConn through the University’s longstanding and unique partnership with the international network Scholars at Risk.